Kevin Frediani

This short introduction to plant names is a deviation from my normal approach to communicating about the diversity and life histories of plants. The first of what I hope will be a short series, this article shares information not only to explore the origin or etymology of a plant name, but also to draw out some of the cross-cultural similarities and differences in the ecological role of plants in their original and cultural landscapes.

The aim is to highlight links that help us better understand human ecology, where human ecology is understood as the relationships between people and their social and physical environments (McManus, 2009). This approach is aligned to work I am enabling in the University of Dundee Botanic Garden, born from a desire to help others cross the psychological barrier to gaining knowledge which is known as ‘plant blindness’ (Allen, 2003, Cothran 2018). This term was cautiously coined by two botanical-educators, James Wandersee and Elizabeth Schussler, in 1998. They define it broadly as ‘the inability to see or notice the plants in one’s own environment, leading to the inability to recognize the importance of plants in the biosphere and in human affairs’.

An anthropology

So, why do I think we need an anthropology of plant names as opposed to the usual approach to helping to ‘simplify’ them, exemplified by Johnson, Smith and Stocksdale (2019)? I hope that this departure from the more traditional reductionist approach to cataloguing nature commonly adopted by western science provides instead a more human story of ‘the naming of names’ – aligned to, but subtly different from, the historical content of Anna Pavord’s book with that title (2005).

This leads to an approach that looks to use the experiential learning gained from working with trees and adopts a somewhat ‘radical’ (see below) way of helping to explain the origin of the names we have given to plants and their parts over time. I hope this ‘two-eyed seeing’ brings interest and pleasure but more importantly sparks curiosity in those who follow this thread.

The etymology of the word ‘radical’ is the Latin word radicalis, which means ‘of or having roots’. The word ‘radical’, which describes the initial underground parts of a developing plant, has evolved to inform a much wider set of potential meanings in our own culture over time. If you are interested in the origins of words then the Etymonline website is a great place to start exploring: www.etymonline.com/word/radical

Two-eyed seeing

Drawing from a social anthropological approach to ‘take the experience of other people – wherever they live, whatever their background, whatever language they speak – to take that experience seriously and learn from it’ (Meistere, 2020), two-eyed seeing is derived from both Cartesian and Goethean approaches to science. Goethean science is itself aligned to more indigenous ways of knowing; it is a philosophical approach to learning associated with the polymath Johann W. von Goethe, a German 18th-century thinker who believed knowledge is best learnt by experiencing the subject. He developed a phenomenological approach to natural history, an alternative to the Cartesian-derived Enlightenment approach to natural science that dominates our way of seeing, or at least describing, the world in formal education today. Crudely put, Goethean science looks to help the observer see the plant in an intimate first-hand encounter (Seamon, 2005), so the thing you’re observing begins to help you understand how to observe. In short, the more you look and engage, the more you see and understand.

Such two-eyed seeing (etuaptmumk in the Canadian indigenous language Mi’kmaw) embraces ‘learning to see from one eye with the strengths of Indigenous knowledges and ways of knowing, and from the other eye with the strengths of mainstream knowledges and ways of knowing, and to use both these eyes together, for the benefit of all’ (Reid et al., 2021).

The naming of names

So that we can begin this immersive journey together, I must start by assuming that you have already been introduced to our dominant cultural approach to the naming of names, where a plant is given a generic name – a ‘collective name’ for a group of plants – and a specific name or epithet. Together these two names are referred to as a binomial.

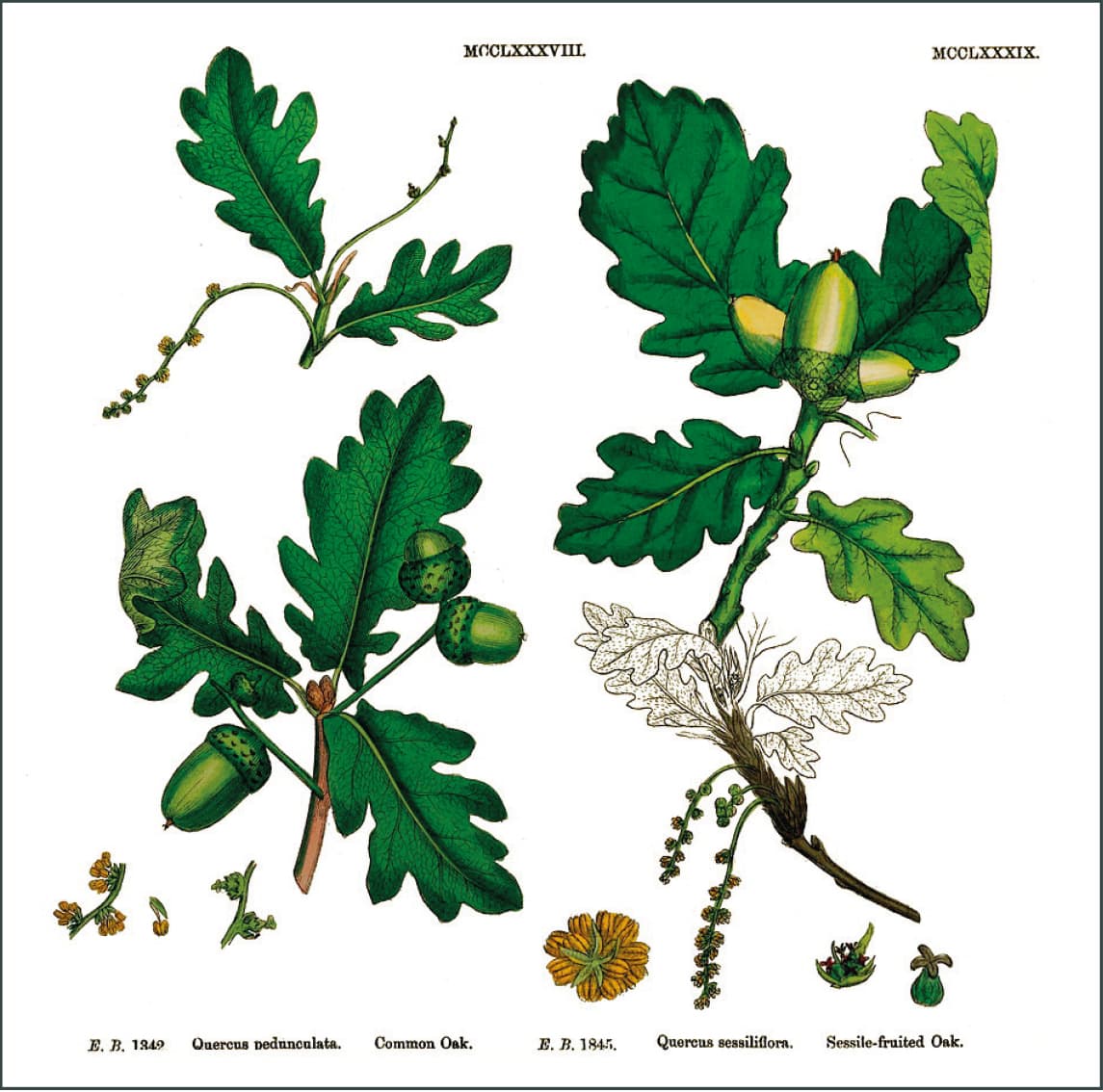

Figure 1: The pedunculate oak (Quercus robur syn. Q. pendunculata) has a shorter leaf stalk (petiole) than the sessile oak (Q. petraea syn. Q. sessilflora), and there are obvious auricles at the leaf base (ear-like projections at the base of the leaf that are absent in sessile oak). The acorns are produced in groups on a long peduncle (stalk that the fruit sits upon), whereas the acorns of sessile oak have no peduncle or a very short one. (Image: https://www.delta-intkey.com/angio/images/ebo12881.jpg).

The generic name indicates a grouping of organisms that all share a suite of similar characteristics. Ideally, they should all have evolved from one common ancestor. The specific name allows us to distinguish between different organisms within a genus. By convention, binomial names are always written with the generic name first, starting with a capital letter and underlined or more often italicised, e.g. Quercus for the oak genera. The specific epithet always follows the generic name, starts with a lower-case letter and is also in italic, e.g. robur.

However, to get to know this plant we have to look beyond its binomial name to what differentiates it from other oaks. The parts that we can easily see include the flowers, fruits, leaves, buds, form and habitat. All these are used in the practical identification of plants (see Figure 1).

Where does this scientific name come from? Quercus as the name of a tree genus is the Latin word for oak; it is derived from Proto-Indo-European (PIE), the theorised common ancestor of the Indo-European language family, which suggests the tree’s long-used original name was kwerkwu-, an assimilated form of perkwu.

What is now commonly known as the oak tree genus has had a long association with the Indo-European cultures. The acorn – which is a nut according to the botanical definition – is the ‘fruit’ of the oaks and their close relatives, acorns being common in two genera: Quercus and Lithocarpus – both members of the higher order family Fagaceae. The Fagaceae are strongly supported by both morphological (especially fruit morphology) and molecular data as a distinct natural plant group (known as a clade). The nut of an oak usually contains one seed (occasionally two), is enclosed in a tough, leathery shell, and is borne in a cupule. It differs from the nuts of the other main members of the Fagaceae commonly grown in the UK, with beech (Fagus sylvatica) having two seeds and sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa) usually having three nuts inside each fruit (Willis, 1973: 452).

In contrast to the Latin name with its ancient origins, the Middle English oke derives from Old English ac ‘oak tree’ and in part from Old Norse eik, both from the Proto-Germanic word aiks (which is also the source for Old Saxon and Old Frisian ek, Middle Dutch eike, Dutch eik, Old High German eih, German Eiche, Swedish ek and Danish eg). It is a word of uncertain origin with no definite link outside Germanic languages.

In his exploration of European grazing ecology and forest landscapes, Frans Vera (2000) suggests that while the origin of the word itself is uncertain, the oak, and more specifically the acorn it produced, was an important commodity and measure in the Germanic cultures which came to dominate Western Europe under a feudal system of land ownership and management. Until the first half of the 18th century, the income generated from acorns was 10–20 times, up to even 100 times, that from wood, which today is something hard to imagine because food is a globalised product, generated intensively someplace else, in farms remote from other land uses – disconnected from people who have lost indigenous knowledge of land uses and language that have been displaced. The special importance of these oak fruit trees to the lords can be related, in the first instance, to the high incomes that could be generated from pannage, which is the practice of allowing pigs to feed on the mast of acorns and other fruits, including below-ground fungi found in the ‘forest’ or ‘wastelands’ beyond the cultivated fields near homesteads (Vera, 2000: 213–215).

The accepted Indo-European base word for oak is deru-, which has become the Modern English word ‘tree’. In Greek and Celtic, however, the words for oak are derived from the Indo-European root for the word ‘tree’. All this probably reflects the importance of the oak, the monarch of the forest, to ancient Indo-Europeans. Likewise, as there were no oaks in Iceland, the Old Norse word eik came to be used by the Viking settlers there for ‘tree’ in general.

The English oak’s specific epithet, robur, is connected with the Latin words robustus, meaning strong and hardy – literally ‘as strong as oak’, ‘oaken’; robur, robus, meaning ‘hard timber, strength’; and also ruber, ‘a special kind of oak’, named for its reddish heartwood. The word ruber is also related to robigo (rust), from the Proto-Indo-European root reudh-, which means red, ruddy.

So, by looking at the Latin origins of its name, we can understand that Quercus robur is the European oak with hard, red heartwood and a rich history that crosses cultures and continues to be relevant and useful over time. In its classification it shares the characteristic of developing a single nut as a fruit with other oaks and the closely related Lithocarpus genera, within the family of Fagaceae (the beech family).

Oak is used here as an example species not only to explain the origin of a common name, but also because it allows readers to chart the imperial imposition of names across cultures and shares something that has been lost from human ecology.

Europeans who came across familiar-looking trees when they emigrated to North America identified them as being in the oak family (Quercus spp) and this has become their accepted name, imposed worldwide through the imperialisation of plant knowledge in the 18th century (Cook, 2009; Lonati, 2013).

The tree was of course already well known to indigenous people as the most important source of hard mast in hardwood forests across North America and had many names long before the arrival of European agriculturalists in the 17th century. Along with the hickory family (Carya spp), oaks were the dominant species in the oak-hickory forest, a type of forest cover that once dominated the eastern woodlands of North America from New York to Georgia and from the Atlantic seaboard to Iowa and north-eastern Texas. The oak-hickory ecosystem had the largest range of any of North America’s native deciduous forests, and indigenous names varied with tribal language; for example, the Apache name ‘Cheis’ meant ‘oak, wood’ (Roberts, 1993).

In addition to being an important food source for wildlife, acorns were also the staple food of California’s American Indian tribes. Nutritious and easy to gather, the acorns were collected, leached to remove the bitter tannins, and pounded into flour to make acorn mush or bread. The naturalist John Muir called these acorn cakes ‘the most compact and strength-giving food’ he had ever eaten (Logan, 2006). European colonists established the tradition of pannage when they came to the Americas, before the advent of 19th-century factory farming systems. Interestingly, it is currently experiencing a revival thanks to the superior flavour and nutritional qualities of the resulting pork.

Figure 2: An ancient open-grown oak tree in Windsor Great Park. One of 3500 open-grown oak trees growing in the grazed landscape of the historic hunting forest that are over 400 years old. (© Kevin Frediani)

Oak in the landscape

Oaks arose an estimated 56 million years ago (mya) and subsequently radiated and expanded across the northern hemisphere (Manos & Stanford, 2001; Hipp et al., 2020). Today they extend from the equator (Colombia and Indonesia) up to the boreal regions to a latitude of 60°N in Europe, and from sea level up to 4000m in the Yunnan province in China (Camus, 1936, 1938, 1952; Menitsky, 2005; De Beaulieu & Lamant, 2010).

The native oaks in the UK are Quercus petraea and Q. robur. Q. robur occurs in 85% of 10km grid squares in Great Britain and Q. petraea in 67%. Oak trees can live for many hundreds of years, and England has more known ancient oaks than the rest of Europe (Farjon, 2017). Oak trees in the UK are a major feature of internationally important habitats, such as the Atlantic rainforests of the west coast which are renowned for their bryophyte and lichen flora (JNCC, 2014). They are shade-intolerant species which do not readily regenerate under their own canopy, requiring germination in open fields adjacent to the parent ‘woodland’ or open-grown trees where their acorns benefit greatly from propagation by animals who seek their rich carbohydrate store. A recent study found that jays and possibly grey squirrels planted more than half the trees in sites that are left without high grazing or human interference (Broughton et al., 2021). Jays and thrushes basically engineer these new woodlands if we don’t interfere.

Shade tolerance is the relative capacity of a tree species to compete for survival under shaded (which is to say less-thanoptimal) conditions. It is a tree trait, a functional adaptation that varies between species. Because of its outsized influence on tree survival and stand growth, shade tolerance is a pillar of silviculture as a plantation approach to managing landscapes, in contrast to the walking woodlands in which oak is best adapted to thrive.

This non-woodland tree canopy is estimated to cover 11% of the urban land area and 3% of the rural land area in Britain (National Forest Inventory, 2017), and Quercus petraea/robur is the second most common non-woodland tree after Fraxinus excelsior (7.7% vs 10.3%) (Forestry Commission, 2001). Half of the ancient oak trees recorded in the UK Ancient Tree Inventory are in non-woodland ecosystems. Thus, oak trees outside woodlands form an important feature of the UK landscape. They are also an important feature of the landscapes they inhabit elsewhere, where corvids and mammals help propagate their lineage (Nuzzo, 1986; Marañón et al., 2009; Gottfried & Ffolliott, 2013).

Taxonomy and conservation of oak

The practice and science of categorisation or classification, known as taxonomy, are complicated, and this is exemplified by oaks that readily hybridise with other oaks within their natural range. The genus Quercus is native to the northern hemisphere and covers evergreen and deciduous species ranges from cold temperate to tropical latitudes in the Americas, Europe, Asia and North Africa. North America contains the most significant number of oak species, with around 90 growing in the US, while Mexico has 160 species, of which 109 are endemic. The second most significant centre of oak diversity is China, which has almost 100 species.

The genus Quercus is considered among the most widespread and species-rich of tree genera in the northern hemisphere, yet due to anthropogenic change it is declining globally because of a combination of emergent pests, pathogens and physiological-induced strain caused by the episodic weather associated with climate change (Mitchell et al., 2019; Kremer & Hipp, 2020). Although the conservation status of more than half of the world’s oak species is currently unclear, work to find out is ongoing through the Global Tree Campaign led by researchers at the Morton Arboretum. They have published a Red List of US oaks and hope to publish a global assessment soon (Jerome et al., 2017; Global Tree Campaign, 2021).

Many oaks are of conservation concern. In 2007 the IUCN/SSC Global Tree Specialist Group published The Red List of Oaks which includes 175 of the roughly 450 species in the genus Quercus worldwide. Of those 175 species, 67 are found inside the US, which is seen to be the global leader in the modern world but is still unable to avoid the decline of these iconic species (IUCN, latest version 2015–16), a task that is actively being progressed through the work of the international community of Botanic Gardens currently (Jerome et al., 2017).

The naming of names by example

I end this article with some examples of Quercus species and their specific epithet meanings. This information is gathered from Johnson, Smith and Stockdale’s Plant Names Simplified: Their Pronunciation, Derivation and Meaning (2019), which is a great book to support your interest in the origins of the names of plants in general and trees in particular.

|

Common name

|

Scientific name

|

Meaning of species epithet

|

| White oak |

Quercus alba |

White, in reference to the light ash-grey bark. |

| Swamp white oak |

Quercus bicolor |

Refers to the leaves being shiny green above and silvery-white beneath. |

| Scarlet oak |

Quercus coccinea |

Scarlet |

| Blue oak |

Quercus douglasii |

A reference to Scottish botanist David Douglas (1798–1834) who discovered this plant during his North American explorations. (Douglas fir is also named after him.) |

| Pin oak |

Quercus palustris |

From the Latin word for marsh (palus), in reference to a common habitat for this tree. |

| Sessile oak, Durmast oak |

Quercus petraea |

From the Latin word petraeus, meaning ‘growing among rocks’. |

| Red oak |

Quercus rubra |

Red |

| Netleaf oak |

Quercus rugosa |

Wrinkled, a reference to the appearance of the foliage. |

| Post oak |

Quercus stellata |

Starlike, probably a reference to the leaf shape, which is actually more cruciform (shaped like a cross) than starlike. |

| Black oak |

Quercus velutina |

Velvety or hairy, a reference to the fine hairs found on buds and young leaves while the common name is a reference to bark colour. |

Kevin Frediani FArborA is the Curator of the Botanic Garden and Grounds, University of Dundee.

References

Allen, W. (2003). Plant blindness. BioScience 53 (10): 926. https://doi.org/10.1641/0006-3568(2003)053[0926:PB]2.0.CO;2.

Broughton, R.K., Bullock, J.M., George, C., Hill, R.A., Hinsley, S.A., Maziarz, M. et al. (2021). Long-term woodland restoration on lowland farmland through passive rewilding. PLoS ONE 16(6): e0252466. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252466.

Camus, A. (1936, 1938, 1952). Les chênes. Monographie du genre Quercus. 3 volumes. Paris, France: Editions Paul Lechevalier.

Cook, G. A. (2009). Linnaeus, Chinese flora and ‘linguistic imperialism’. The 2009 Symposium of the University of Hong Kong Summer Institute in Arts & Humanities: ‘The Appropriation of Chinese Nature during the Enlightenment’, Hong Kong, China, 14 July. Accessed: 19/09/2021: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/37949439.pdf.

Cothran, M. (2015). Plant blindness: why scientists who know nature are becoming an endangered species, Memoria Press. Accessed: 19/09/2021: https://www.memoriapress.com/articles/plant-blindness-why-scientists-who-know-natureare-becoming-an-endangered-species/.

De Beaulieu, A. and Lamant, T. (2010). Guide illustré des chênes. Geers, Belgium: Edilens.

Farjon, A. (2017). Ancient Oaks in the English Landscape. Surrey, UK: Kew Publishing.

Forestry Commission (2001). Inventory Report: National Inventory of Woodland and Trees – England. Forestry Commission.

Global Tree Campaign (2021). Red Listing the Worlds Oak Species. Accessed: 20/09/2021: https://globaltrees.org/projects/red-listing-oaks/.

Gottfried, G.J. and Ffolliott, P.F. (2013). Report: Ecology and management of oak woodlands and savannas in the southwestern Borderlands Region. In: Gottfried et al. (2013). Merging Science and Management in a Rapidly Changing World: Biodiversity and Management of the Madrean Archipelago III. Fort Collins, CO: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. pp. 337–340. Accessed: 19/09/2021: https://www.fs.fed.us/rm/pubs/rmrs_p067/rmrs_p067_337_340.pdf

Hipp, A.L., Manos, P.S., Hahn, M., Avishai, M., Bodenes, C., Cavender-Bares, J., Crowl, A., Deng, M., Denk, T., Gailing, O. et al. (2020). The genomic landscape of the global oak phylogeny. New Phytologist 226: 1198–1212.

Ingold, T. (2018). Why Anthropology Matters. Cambridge: Polity Press.

IUCN (2015–16). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2015-4. Available at: www.iucnredlist.org.

Jerome, D., Beckman, E., Kenny, L., Wenzell, K., Kua, C.-S., Westwood, M. (2017). The Red List of US Oaks. Lisle, IL: The Morton Arboretum.

Johnson, A.T., Smith, H.A. and Stockdale, A.P. (2019). Plant Names Simplified: Their Pronunciation, Derivation and Meaning,<,em> 3rd edition. Sheffield, UK: 5M Publishing.

JNCC (2014). EC Habitats Directive. Accessed: 18/09/2021: http://jncc.defra.gov.uk/page-1374

Kremer, A. and Hipp, A.L. (2020). Oaks: an evolutionary success story. New Phytologist 226(4): 987–1011.

Logan, W.B. (2006). Oak: The Frame of Civilisation. London & New York: W.W. Norton.

Lonati, E. (2013). Plants from abroad: botanical terminology in 18th-century British encyclopaedias. Accessed: 19/08/2021: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/187916003.pdf.

Manos, P.S. and Stanford, A.M. (2001). The historical biogeography of Fagaceae: tracking the tertiary history of temperate and subtropical forests of the Northern Hemisphere. International Journal of Plant Sciences 162: S77–S93.

Marañón, T., Pugnaire, F.I. and Callaway, R.M. (2009). Mediterraneanclimate oak savannas: the interplay between abiotic environment and species interactions. Web Ecology 9: 30–43.

McManus, P. (2009). Ecology. In Audrey Kobayashi (ed.), International Encyclopaedia of Human Geography, 2nd edition. Pp. 15–23. London: Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-102295-5.10007-1.

Meistere, U. (2020). Anthropology, art and the mycelial person in conversation with Tim Ingold. Accessed: 19/09/2021: https://spiriterritory.com/conversations/interviews/24992-anthropology_art_and_the_mycelial_person.

Menitsky, Y.L. (2005). Oaks of Asia. New York: CRC Press.

Mitchell, R.J., Bellamy, P.E., Ellis, C.J, Hewison, R.L., Hodgetts, N.G., Iason, G.R., Littlewood, N.A, Newey, S., Stockan, J.A. and Taylor, A.F.S. (2019). Collapsing foundations: The ecology of the British oak, implications of its decline and mitigation options, Biological Conservation 233: 316–327, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2019.03.040.

Nuzzo, V.A. (1986). Extent and status of Midwest oak savanna: Presettlement and 1985. Natural Areas Journal 6(2): 6–36. Accessed: 19/09/2021: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43910878.

Pavord, A. (2005). The Naming of Names: The Search for Order in the World of Plants. London: Bloomsbury.

Reid, A.J., Eckert, L.E., Lane, J.-F., Young, N., Hinch, S.G., Darimont, C.T., Cooke, S.J., Ban, N.C., and Marshall, A. (2021). ‘Two-Eyed Seeing’: An Indigenous framework to transform fisheries research and management. Fish and Fisheries 22: 243–261. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12516.

Rouhan, G., and Gaudeul, M. (2021). Plant taxonomy: A historical perspective, current challenges, and perspectives. Methods in Molecular Biology 2222: 1–38.

Roberts, D. (1993). Once They Moved Like the Wind. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Seamon, D. (2005). Goethe’s way of science as a phenomenology of nature JANUS HEAD 8 (1).

The Woodland Trust. The UK Ancient Tree Inventory. Accessed: 19/09/2021: https://ati.woodlandtrust.org.uk/.

Vera, F.M.V. (2000). Grazing Ecology and Forest History. Wallingford, UK: CABI Publishing.

Wandersee, J.H., and Schussler, E.E. (1999). Preventing plant blindness, The American Biology Teacher 61(2): pp. 82–86.

Willis, J.C., revised by Airy Shaw, H.K. (1973). A Dictionary of Flowering Plants and Ferns, 8th edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

This article was taken from Issue 195 Winter 2021 of the ARB Magazine, which is available to view free to members by simply logging in to the website and viewing your profile area.