Michael Grindley

1. An Asian hornet. (© David Walker via www.nonnativespecies.org)

2. Asian hornet and potential lookalikes. (© APHA)

Since 2004, Asian hornets (Vespa velutina nigrithorax) have slowly but steadily established themselves in Europe and spread to all of France, Portugal and northern parts of Spain. They are now moving into Holland, Belgium and Germany.

The Asian hornet is a highly aggressive predator of native insects and poses a significant threat to all pollinators, including honey bees.

The link in the footnote below* will open a time lapse showing the establishment and spread of the Asian hornet in Europe. Note the outbreaks in some years that are some distance away from the advancing front.

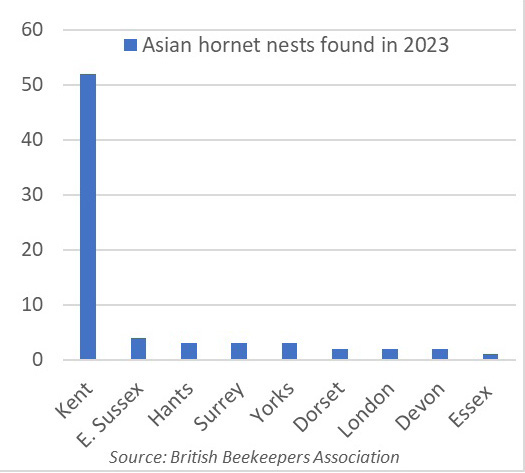

Since 2016, sporadic incursions into mainland Britain have occurred but were few in number and all were destroyed. However, in 2023, a total of 78 nests were found and destroyed. This is a sevenfold increase on any previous year.

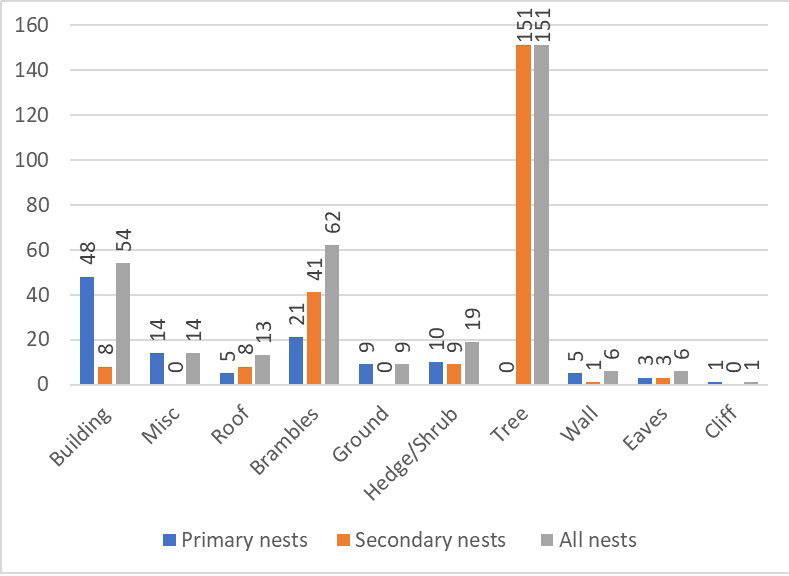

Why am I writing this article for the Arboricultural Association? Well, on the Island of Jersey, they found 338 nests in 2023 and 45% of those were in trees, with 32% being at heights above 10 metres. Having tracked Asian hornets on Jersey, I know from personal experience that their nests are very difficult to spot, even when you are 100% certain the nest is in a particular tree. Last year, on Jersey, a further 24% of nests were discovered in brambles, hedges and shrubs.

You might now be beginning to understand my concern for you.

I am trying not to be an alarmist, as the chances at this point in time of encountering a nest are small, but the nests found in 2023 are indicative of what we can expect to come in the future when Europe experiences another ‘surge year following a mild winter, such as the winter of 2022/23. The number of nests will increase exponentially should Defra (APHA) be unable to prevent the insect from becoming established.

Should you climb a tree and discover the Asian hornet has taken up residence in the same tree or, in a wooded area, even the adjacent tree, you can expect them to be extremely aggressive by the time you realise there is a nest. Their stings are, I am told, extremely painful and the insect has a habit of flying at the perceived threat and stopping short of flying into it and then, while hovering in front of the intruder, voiding its bowels, effectively spraying the intruder with a fine mist of faeces. If this manages to enter the eyes, it results in a burning sensation and is very uncomfortable but is easily removed with a water flush.

The advice from France on what to do if you unexpectedly encounter a nest close by is to cover your head and face with your arms and run! Now, up a tree, with Asian hornets bombarding you, stinging and also spraying faeces, are you going to be able to take that advice to run?

Above: 3. Statistics from Jersey States report to Jersey Asian Hornet Group on types of locations where nests were discovered in 2023. (John de Carteret, Jersey Asian Hornet Group)

Above: 4. Statistics from the British Beekeepers’ Association on the distribution of nests within the UK in 2023. (BBKA)

I recommend that you enhance your examination of a tree about to be climbed or a shrub about to be trimmed by looking for ‘traffic’ flying in or out. Stand with the edge of the tree in silhouette and look at the sky adjacent to the tree. Spotting activity by a dark insect moving in or out from the foliage will indicate the presence of a nest which you might need to really look hard to find. Be aware the insects may only be leaving or entering the tree in one or two places in the tree’s circumference, so the examination should be made all around the tree. Take your time with this. Hopefully, you will find the nest is that of the European hornet, or wasps, or even bees.

With reference to current PPE, the flip down visor attached to your helmet will not provide sufficient protection to your eyes. The advice from Jersey and France is to use goggles that completely cover the eyes. Climbing a tree with a known nest will also require a full body protective suit, helmet and gloves thick enough to prevent stings from penetrating to your skin.

5. A primary nest. The presence of the queen gives an indication of scale. (© John de Carteret, Jersey Asian Hornet Group)

6. An example of a mid-sized secondary nest. (©John de Carteret, Jersey Asian Hornet Group)

Life cycle and nests

Like the native European hornet species present in the UK, the Asian hornet queen emerges from hibernation in spring and sets about establishing a primary nest where she will raise the first cohort of workers. Once these have emerged, they will take over the work of nest building and foraging for protein to feed the next batch of young larvae.

As winter approaches, the queen will lay male drones and then female queens. These virgin queens will mate and then leave the nest in search of somewhere to hibernate during the coming winter.

With having to build a nest, feed and incubate the larvae/pupae, the queen takes a few months to raise the first cohort, but thereafter the nest expands rapidly. At some stage, the insects will decide to either relocate to a more suitable location and build a secondary nest, which is usually fairly close to the primary nest, or sometimes they will just expand the primary nest.

On the Island of Jersey, the experience has been that about 80% of primary nests are on or in man-made structures and 20% in natural vegetation. With secondary nests, the ratio swings the other way with about 80% being in natural vegetation and most of those, as already stated, will be in trees, bramble, hedges or shrubs.

The primary nest is small, about the size of a small grapefruit, while secondary nests can be very large with up to 6,000 workers, being about the size of a large suitcase that travellers check in as hold luggage at the airport. The primary nest resembles the nests wasps build, with an entrance at the bottom (photo 5). Secondary nests are quite distinctively different to those of European hornets or wasps, oval in shape with the long axis in the vertical plane, with an entrance at about the equator or slightly below the equator (photo 6). The NNSS (Non-Native Species Secretariat) has produced a guide to Asian hornet nest identification which can be downloaded here: www.bit.ly/48TsfHM.

One of the problems we face is that one cannot predict with any certainty where the queens will emerge. They can fly up to 60 kilometres from their birth place but the newly mated queens are adept at stowing away in or under cargo or vehicles in order to hibernate. This cargo and/or vehicle may then move some considerable distance from the ‘front line’. We can see this type of local outbreak in the location of nests away from Kent in Plymouth etc. in the time lapse mentioned above.

If a traffic light system were to be adopted to indicate the likelihood of a nest being discovered, then in 2024 Kent would be in the red zone, most of the rest of England and Wales would be amber and Scotland would be green. I’ll stop here.

In conclusion, please be vigilant, especially if you do any work in Kent, but please bear in mind that this insect can pop up anywhere, even in Scotland.

Going forward, the news networks will be carrying stories on how the Asian hornet is spreading and at some stage the authorities may release a statement that the presence of the Asian hornet is now considered to have passed the containment phase and is to be considered as being in the establishment phase. When that happens, I hope you will remember this article and double down on your pre-work inspection of the tree(s) to be worked on.

Michael Grindley is the Asian Hornet Coordinator for the Cornwall Beekeepers Association (cbka.aht@gmail.com)

This article was taken from Issue 204 Spring 2024 of the ARB Magazine, which is available to view free to members by simply logging in to the website and viewing your profile area.