Do you know how a branch is attached to the trunk of a tree?

If not, don’t you think you should?

Recent published research from Myerscough College and the University of Manchester has provided us with a clearer picture of the anatomy of junctions in trees. For the Arboricultural Association, lead research Dr. Duncan Slater will be providing a number of Fork Workshops around the UK this summer and autumn, as it is felt that this is a very important area of technical knowledge for our members to get to grips with.

Junctions in trees vary in their size and anatomy, but typically have a number of features in common. The most important anatomical feature for strengthening a junction is the presence of tortuous, twisted and dense wood grain down the central seam of the join between the two conjoined limbs – the location of which can be seen externally by the presence of the branch bark ridge.

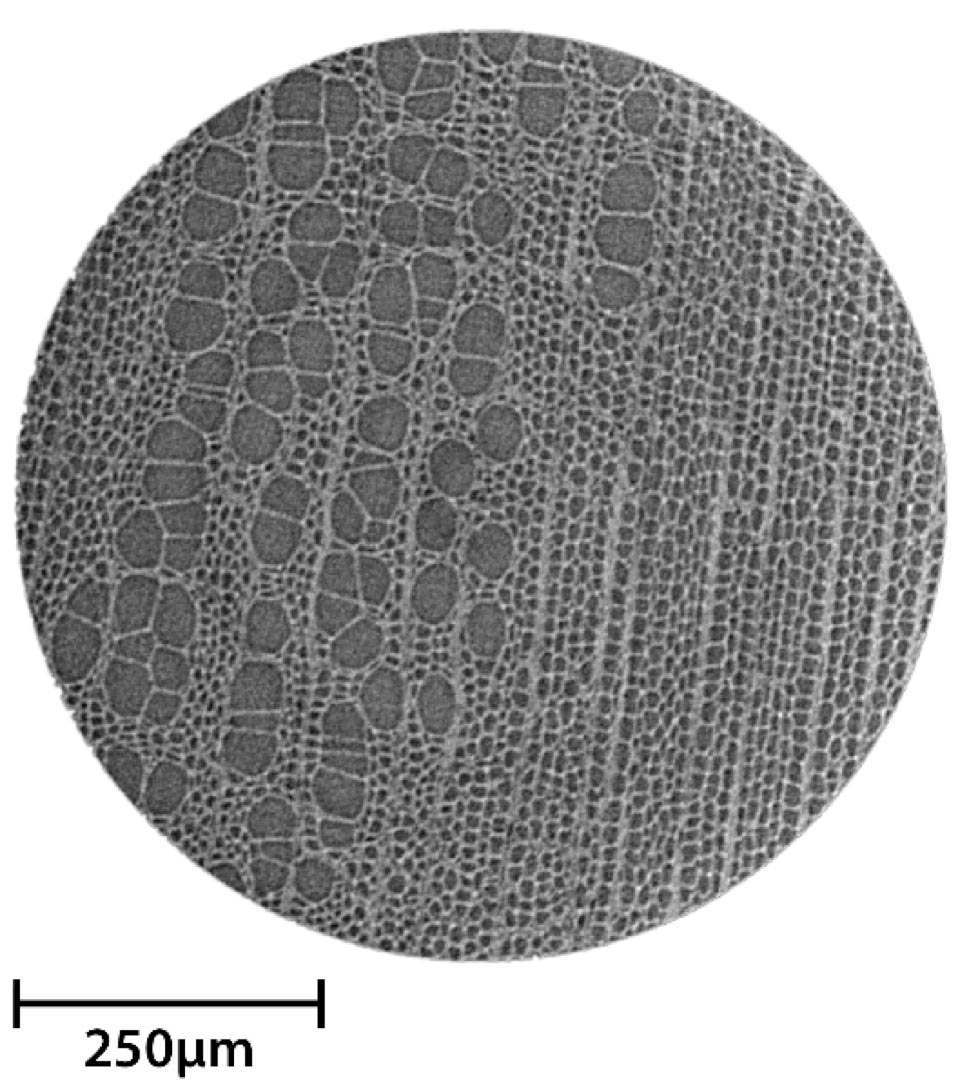

Stem wood of hazel (Corylus avellana L.) in cross-sectional view (CT scan image courtesy of MXIF)

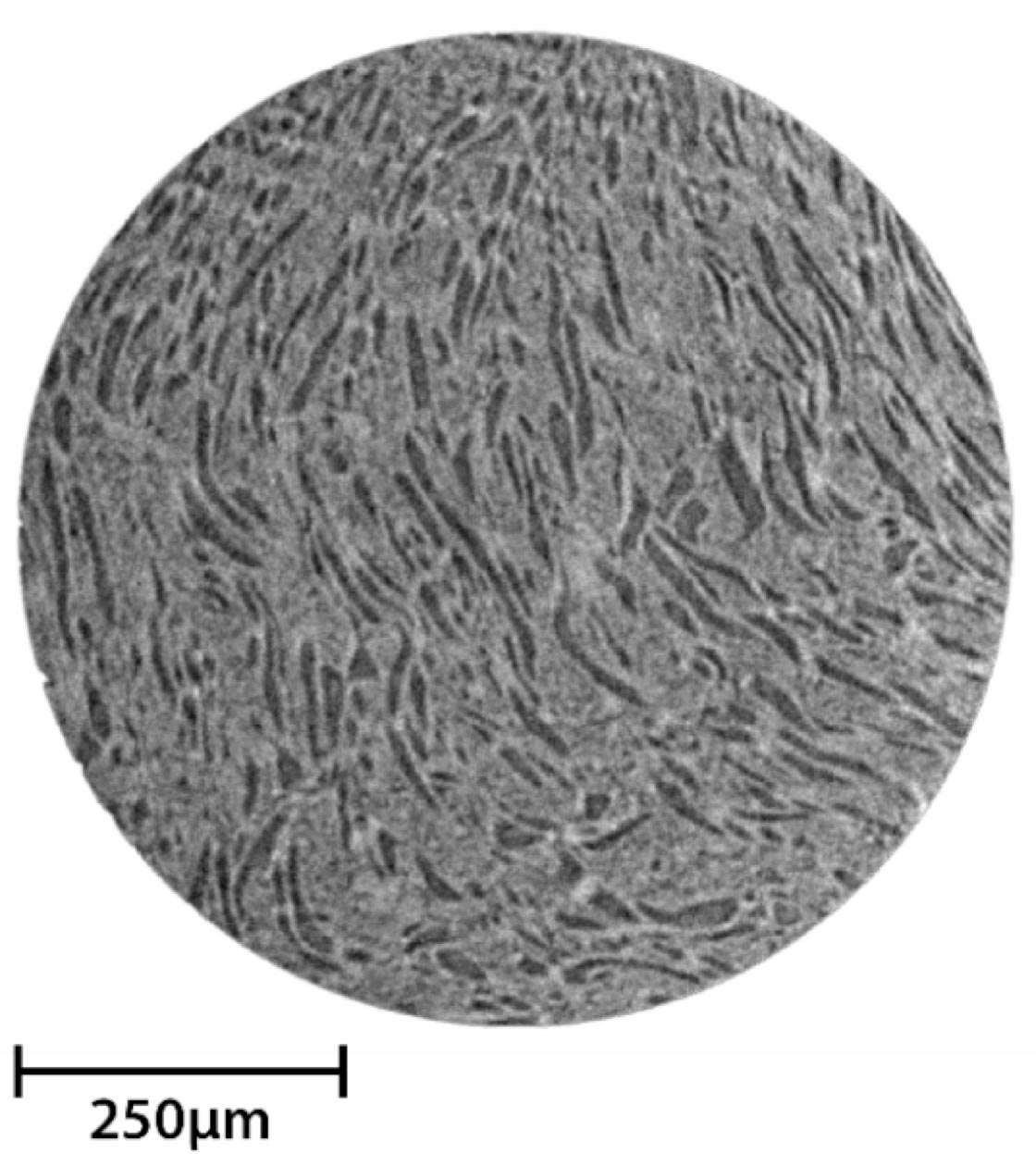

Twisted wood formed at the centre of the branch bark ridge in hazel, in comparison (MXIF, 2012)

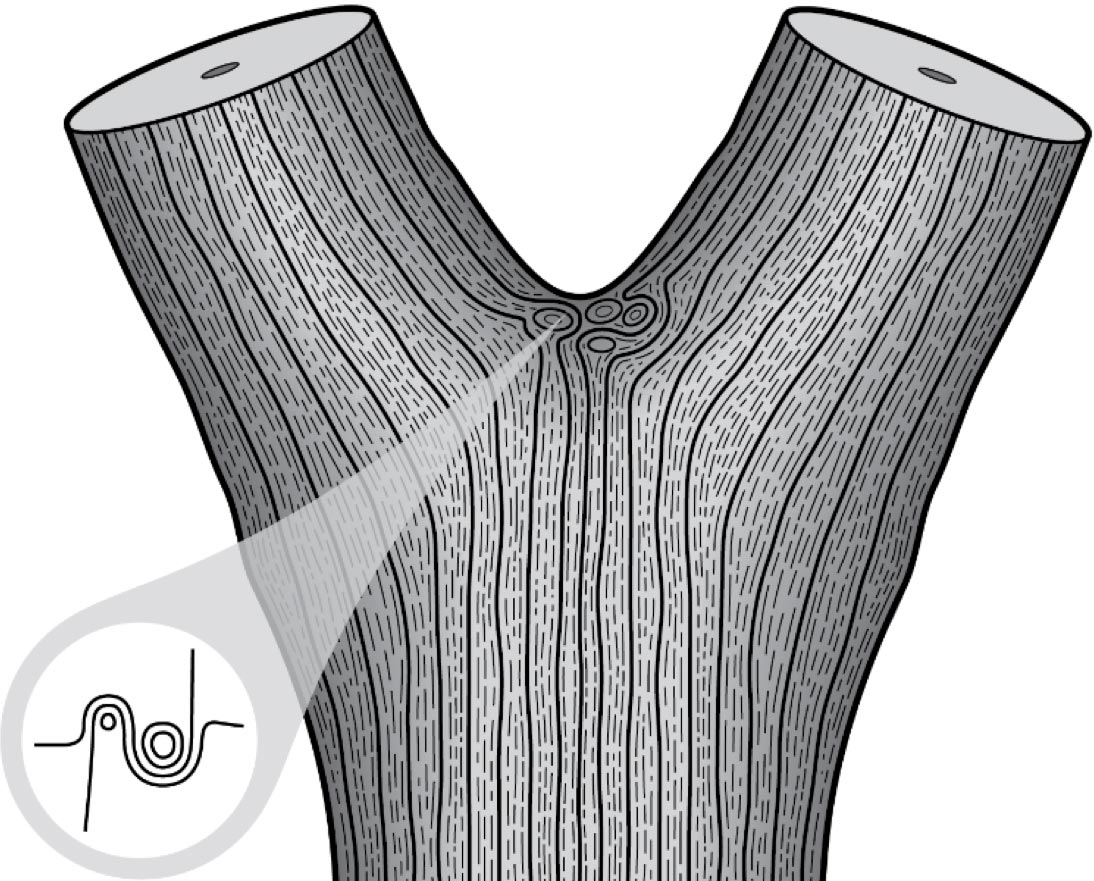

Whirled wood grain pattern forming an interlock between two limbs in a mature oak tree

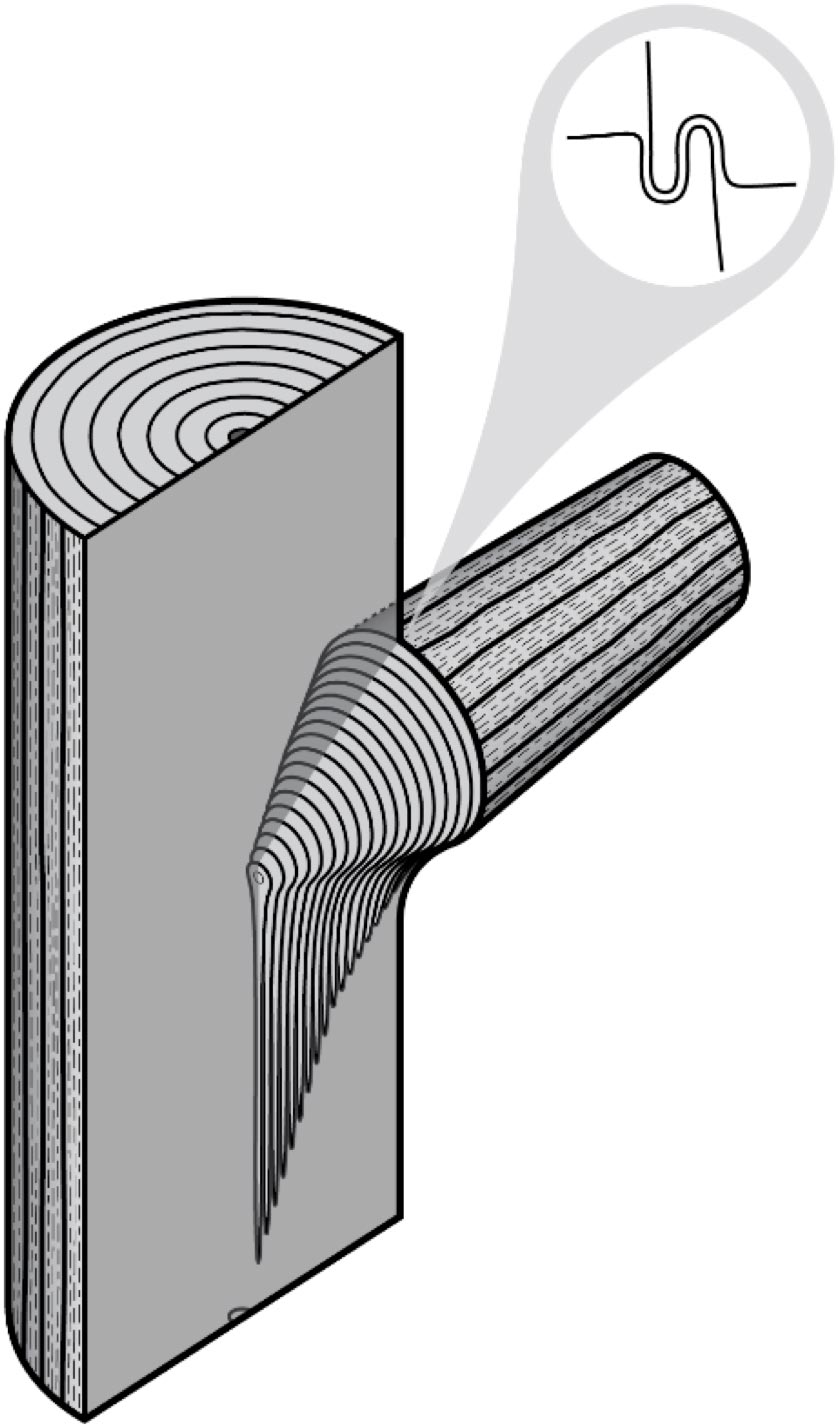

In most junctions, this centrally-placed wood grain forms an interlocking pattern – so it is necessary to snap wood fibres along their length or to extract them from adjacent wood in order to break the junction. You can see this feature by eye in many tree species if you strip the bark off around a branch attachment, and many of you may well have experienced that this twisted and dense material is much more difficult to split when firewooding.

Perhaps, though, you have never really thought of this as the way in which branches of trees are ‘stitched together’

Where a small branch joins a larger stem, the older part of the branch becomes occluded (‘swallowed up’) by the tree’s trunk to form a knot. Where two branches of roughly equal size join in the crown of a tree, forming a ‘fork’, there is no supporting knot, and the interlocking wood grain patterns are essential to stabilise these joins.

Interlocking grain and knot formation in a branch-to-stem attachment

Interlocking grain in a branch-to-branch attachment (aka ‘a tree fork’)

Where bark is included into the junction, this interlocking and tortuous wood grain can be absent, making such a branch attachment substantially weaker.

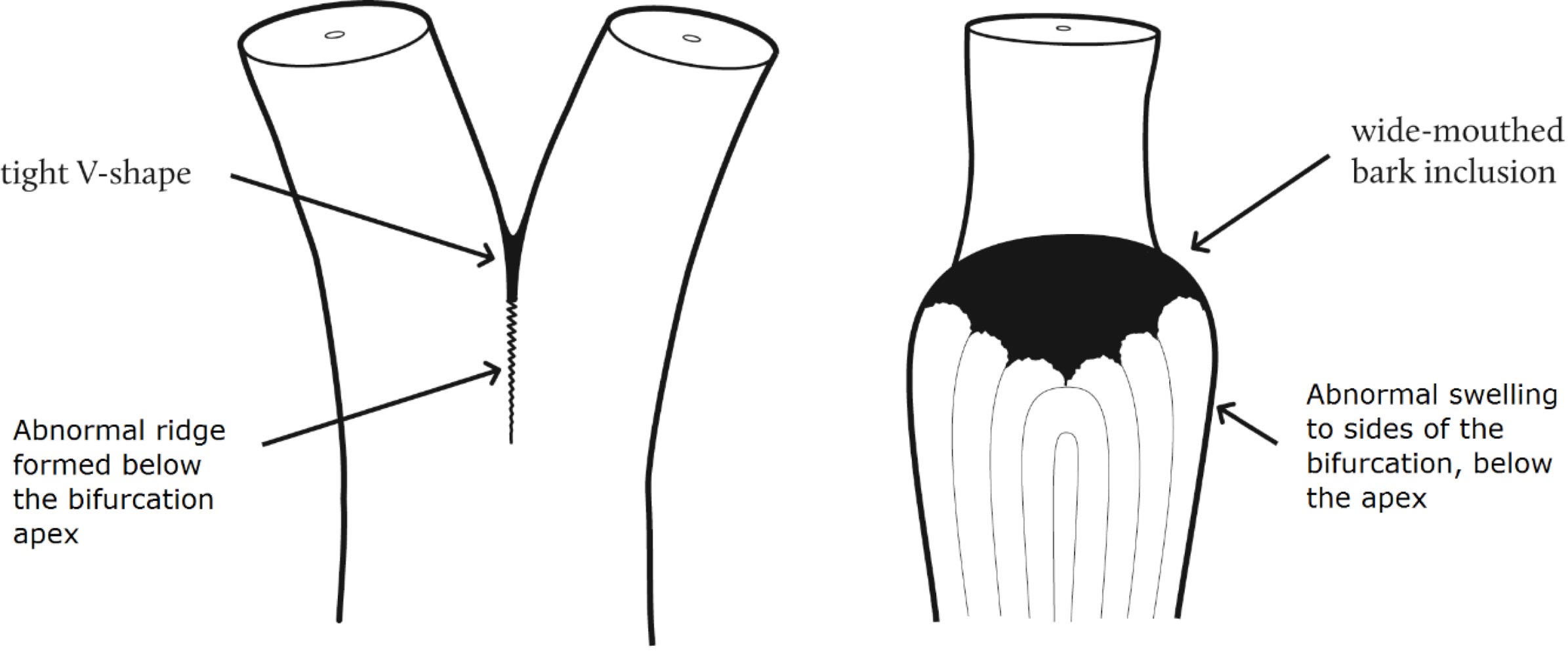

A. Bifurcation with wide-mouthed bark inclusion, typically 42% weaker than normally-formed bifurcations.

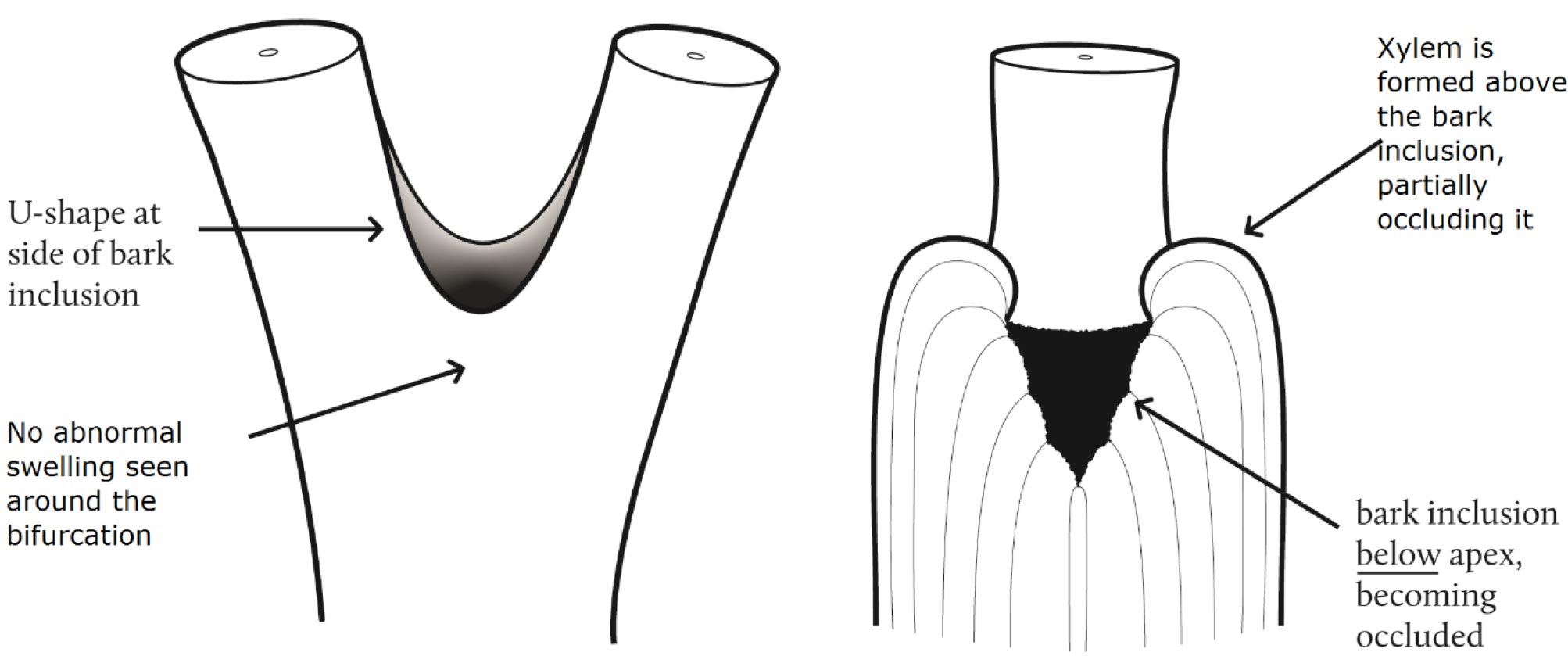

B. Cup-shaped bifurcation with bark being occluded by xylem growth, typically 21% weaker than normally-formed bifurcation.

At our “Assessment of Tree Forks” workshops, Dr. Slater will provide guidance on how to professionally assess junctions in trees for their safety, he will supply many images and examples from his research showing the anatomy of junctions and he will be reporting on his most recent research work as to how bark-included junctions are formed and how they are associated with ‘natural braces’. This one day course will provide delegates with very valuable new knowledge on the very recent research in this area, as well as introducing a framework for predicting the failure of suspect bark-included junctions.

Date & Venues

Branch supported workshop dates and locations:

Click a date to book.

|